News & Announcements

Tail-wagging tomography: Meet the nuclear medicine alums behind your pet’s scans

Sept. 12, 2024

Story by Ryan Gauthier, rjgauthier@health.missouri.edu

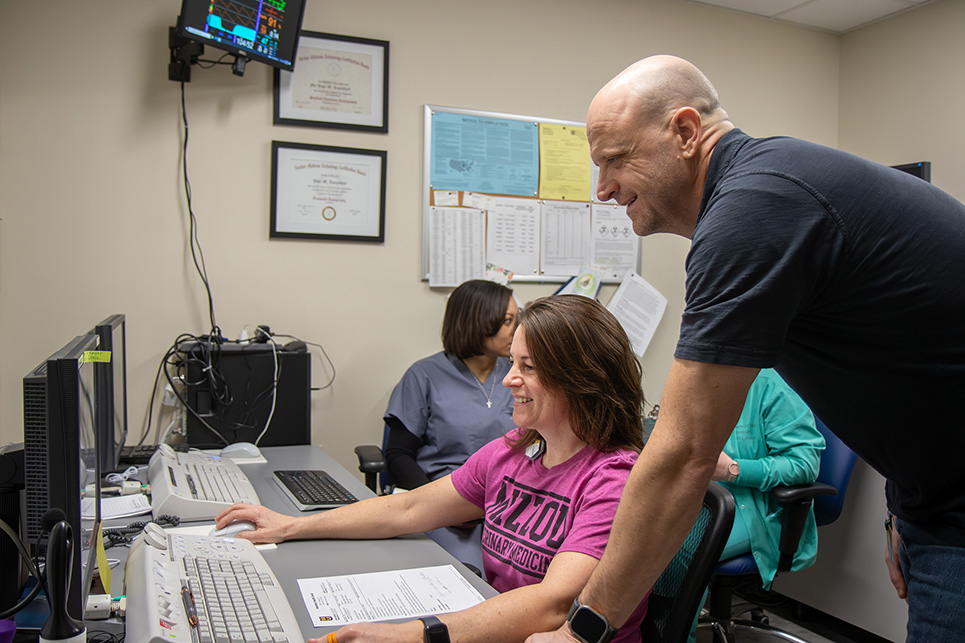

When Joni and Kevin Lunceford graduated from the University of Missouri with degrees in nuclear medicine (Joni in 2002 and Kevin in 1995), they didn’t anticipate using their skills to help four-legged patients.

The Luncefords were both undergraduates in the School of Health-Related Professions — before it became the College of Health Sciences — and said they were drawn to nuclear medicine because it enabled them to work with cutting-edge technology while also interacting directly with patients.

“I found it satisfying that some of the changes you can make on the imaging parameters for nuclear medicine could really affect the final product,” Kevin said. “I didn’t want to just be pushing a button on a machine; I wanted to understand the technology and work to produce the best images possible.”

The Missouri natives — Joni from Jefferson City and Kevin from the small town of Cosby near St. Joseph — worked with human patients for years at multiple locations throughout Missouri as well as in Napa, California. Their careers eventually brought them back to Missouri. After they returned to the Nuclear Medicine department at the University of Missouri, the Mizzou Veterinary Health Center reached out to see whether Kevin knew of anyone who would do positron emission tomography (PET) scans on animals.

“He called me immediately, and I was like, ‘Who do I need to call? Where and how do I get this job?'” Joni said. “I had wanted to be a veterinarian when I was a small child, so this role was just a perfect fit for me. I had no idea that I’d ever have an opportunity to do nuclear medicine for animals.”

Several years after Joni started working at the Mizzou Veterinary Health Center, Kevin found himself considering a similar career change. It just so happened that the Veterinary Health Center decided to create a position for a radiology supervisor. When he toured the facility during his interview, he was shocked by the incredible resources available.

“I remember leaving this place just amazed at the amount of imaging equipment that was in this building,” Kevin said. “I think most people that tour this building leave here feeling the same way.”

We connected with Kevin and Joni to talk about their transition from human to animal nuclear medicine, the challenges of working with patients who don’t speak your language, and why they couldn’t see themselves doing anything else.

How common of a career pathway is veterinary nuclear medicine?

Joni: “It’s absolutely uncommon. There aren’t many places in the country that do what we do. When people want to get something unique done for their pets, we are usually the ones to do it. As far as PET-CT goes, to my knowledge, there are only seven veterinary PET-CT locations in the U.S. We’ve had dogs flown in from California, Texas — all over the country.”

How does nuclear medicine with animals differ from human patients?

Kevin: “When you’re caring for patients here at the Veterinary Health Center, they don’t understand your language. A human patient is very motivated to hold still because it’s in their best interest, but in most cases, our animal friends are trying to do exactly the opposite of what you want them to do.”

Joni: “I might have been able to complete a human bone scan in 30 minutes, but an equine bone scan usually takes me two to three hours to do the whole body. It’s incredibly labor-intensive. You’re really working with that horse to try and get it to stay still during image acquisition and then move around to exactly where you need it for the next image. Following any nuclear medicine or PET/CT procedure, the patient must stay in our radiation isolation areas. The length of their stay depends on what isotopes were used for the exam or therapy.”

Did your experiences translate well from humans to animals?

Kevin: “After doing human nuclear medicine for so long, having a change and a challenge is a great thing. Thankfully, the fundamental knowledge that we picked up from doing human nuclear medicine still applies. Joni has a great understanding, knowing that motion and distance from the camera are our major enemies. She does a great job of applying those abilities that we perfected with human patients to get the best images we can here.”

What is the best part of your job?

Joni: “Everyone in this building wants to do the same thing and has the same goals. Veterinary medicine tends to be a lower-paying job, so everyone is here because they want to be here. We’re all here because we love animals and love what we do. You can walk up and have a conversation with anyone in this hospital, and there are endless cute animals around us that you can snuggle when you’re having a bad day.”

Kevin: “It’s a very cooperative environment. There is an appreciation for what everybody brings to this building. [At some jobs,] you’re a nuclear medicine technologist and that’s kind of your lane. Whereas here, you will have faculty members or veterinarians come to you and ask if they can get your opinion on something.”

How did your time at Mizzou prepare you for your career?

Kevin: “The education I received through the nuclear medicine program gave me a good, well-rounded set of tools that have allowed me to pursue various opportunities in the medical imaging field. There are always other avenues in health care that you might find yourself in; I always tell students that you have plenty of options after graduation. There are hospital settings, clinical settings, vendors trying to sell equipment, or even research. It really opens up a number of potential pathways.”

Joni: “Going through the program at Mizzou and then working at University Hospital gave me a strong background in general nuclear medicine. The connections I made through both of those experiences have helped me throughout my career. Having the University of Missouri Research Reactor as well as the chemistry group here really lends itself to anything you might want to do as far as research goes. We have a phenomenal community of people at Mizzou where we can all work together to provide care for our companion animals and pursue research that may lead to future diagnostic and treatment options for animals and humans alike.”